The World Health Organization (WHO) establishes that health is “not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” but rather “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being.” This is especially relevant in the case of elderly people, for whom these different elements are frequently precarious. To this we can add that aging is an extremely heterogeneous process, in which a person’s chronological age alone is a poor indicator of health status. There are 70-year-olds with a cellular and metabolic age comparable to a person of 50, and 40-year-olds who, at the cellular and metabolic level, seem much older.

There are many different ways to define healthy aging, however, the general consensus is that it includes the following elements: a low level of co-morbidity, a high level of social interaction, good functionality and autonomy. Thus, depending on the person’s overall state of health and the degree of independence, there are “elite” elderly people and “frail” elderly people.

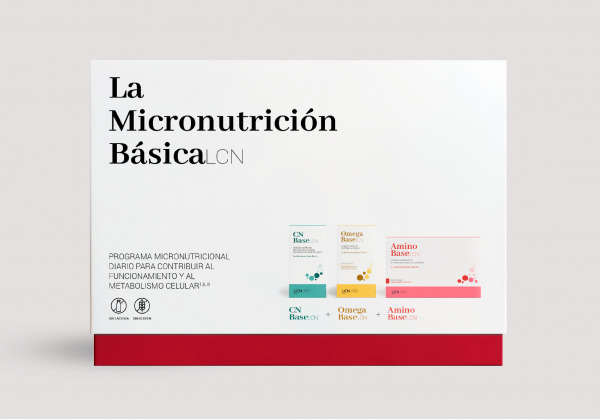

The alterations in the sense of taste and smell, functional disabilities and social isolation that accompany aging predispose people to inappropriate dietary habits and/or imbalances between nutrient intake and individual needs. This has a series of consequences, such as weight loss, alterations of the immune system, worsening of the underlying health condition, longer hospital stays and repeated admissions, and poorer quality of life. This is what we call a frail elderly person, and adequate basic micronutrient intake is paramount in this case.

Meydani M. Nutrition interventions in aging and age-associated disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Apr;928:226-35. Review. PubMed PMID: 11795514.